Coal’s Long Goodbye: Why America Isn’t Turning Back

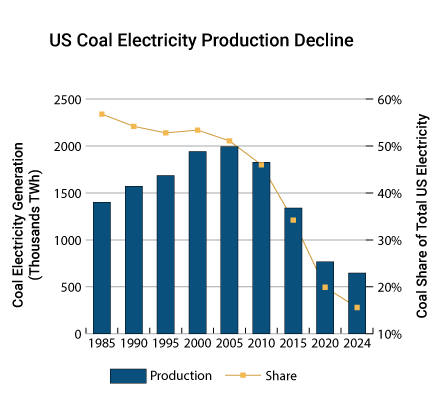

The chart below tells the story in one glance.

Why not use more coal to meet U.S. electricity needs?

On paper, the case looks tempting. The United States holds nearly a quarter of the world’s proven coal reserves—enough to last for centuries. For much of the 20th century, coal was the backbone of American electricity, powering homes, factories, and cities at scale.

But coal’s dominance is firmly in the past.

Coal-fired electricity peaked in 2007, and its decline since then has been steep. By 2024, coal supplied just 16% of U.S. electricity, down from 57% in 1985 (see the figure above). The reasons are not primarily ideological—they’re economic and structural.

Coal struggles on multiple fronts. Environmental impacts remain significant, from air pollution and water contamination to land disruption and greenhouse gas emissions. At the same time, coal has been outcompeted by cheaper natural gas, rapidly falling renewable energy costs, and policy incentives that favor cleaner generation.

Political efforts to revive coal—most notably during the Trump administration—have slowed some plant retirements, but they haven’t changed the underlying math. A broad-based coal resurgence remains unlikely. In many cases, utilities find it more viable to convert coal plants to natural gas rather than continue burning coal.

Other countries have tried a different path. China invested heavily in advanced coal technologies, such as supercritical plants and integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC), improving efficiency and lowering emissions. The U.S., however, is unlikely to follow suit at scale—unless other options fail due to unforeseen reasons.

There is one wildcard: data centers. If electricity demand surges even more than expected, Big Tech could choose to shed its green wannabe credentials and co-locate with existing or recently closed coal plants in regions like West Virginia. Still, this would be a stopgap, not a permanent renaissance.

The most likely outcome over the next decade is not a coal comeback, but a slower pace of retirements. As of mid-2025, utilities had already delayed roughly 12 GW of coal capacity that was slated for closure—using coal as a temporary pressure relief valve for regional grid bottlenecks.

Bottom line: delaying coal retirements may buy time and flexibility, but coal itself is no longer a forward-looking solution. Its role in the U.S. electricity mix is shrinking—and that trend is unlikely to reverse.

Want the bigger picture?

This analysis is part of a broader look at how the U.S. power system is navigating surging demand, grid constraints, and technology tradeoffs.

👉 Reserve your early copy of Power Plays: How the Battle for Electrons Will Define the 21st Century —available for a limited number of early readers.